Incident Update 7︱Canadians’ Views on Political Violence and Freedom of Expression: Reality, Risks, and Misperceptions

Authors & Organization

Eric Merkley

Organization: Media Ecosystem Observatory & University of Toronto

Key takeaways

Canadians’ support for political violence is extremely low, though not for all types of political violence. Between 3-4% of Canadians report support for egregious acts of political violence by those who share their political views, like arson and assault with a deadly weapon. Support rises slightly for assault (9%) and vandalism (12%) and is considerably higher for harassment (25%).

Canadians tend to exaggerate support for political violence among their political opponents, and these exaggerated perceptions are themselves associated with support for political violence. On average, Canadians accurately perceive levels of support for political violence among different partisan and ideological groups in society, but tend to overestimate support for political violence by 100% or more among their political opponents. People with the most exaggerated beliefs report between 2-3 times higher support for political violence.

Most Canadians believe there should be consequences for advocating for political violence but are divided on how severe those consequences should be. 56% of Canadians are willing to tradeoff civil liberties so that governments can address the threat of political violence. About one-third of Canadians believe there should be professional sanctions or legal prosecution for those who justify or celebrate political violence, which rises to 43-53% for those who incite political violence. Still, 20% of Canadians believe there should be no consequences for those who incite political violence, rising to 24-28% for those who celebrate or justify such violence.

Most Canadians perceive freedom of expression to be under threat but are divided on how often they consider the consequences of speech when they post opinions online. 56% of Canadians believe freedom of expression is under serious or moderate threat in Canada. Among those who post about politics online, roughly half think about possible harassment or the professional, legal, and social consequences of doing so before expressing (or failing to express) their opinions online.

An overwhelming majority of Canadians have not faced legal, professional, or social consequences for expressing their political opinions. 79% of Canadians report suffering no consequences for expressing political opinions. Only 3-4% have faced legal or professional consequences, while a slightly higher proportion report social conflict or harassment resulting from their speech (8-10%). These patterns may not indicate the absence of risk, but could also reflect chilled speech, with some avoiding political expression due to concern about possible repercussions.

Introduction

Context

Polarization is rising in both Canada and the United States. People are becoming increasingly resentful of people they disagree with politically, a phenomenon known as affective polarization. At the same time, acts of political violence have been on the rise in the United States, leading to concerns this trend could spill over to Canada. In IU3, we found that while Canadians perceive the threat as less severe than in the United States, half still consider it a serious issue at home, and a third expect it to worsen in the upcoming years.

Combating political violence and the incitement of such violence has implications for civil liberties and freedom of expression – itself a growing area of contention as polarization fuels a trend towards cancel culture, where people impose professional, legal, or social consequences for speech that is deemed unacceptable. Studying how Canadians make tradeoffs between opposing and combating political violence and protecting freedom of expression can inform approaches to prevent the spread of political violence north of the border.

Key questions

This report evaluates the following questions:

How high is support for political violence in Canada, and how does it vary depending on the severity of the crime?

Do Canadians overestimate their political opponents’ support for political violence? Are these misperceptions associated with their own willingness to endorse such actions?

What consequences do Canadians support for those who incite or justify political violence?

Do Canadians perceive freedom of expression to be under threat in Canada? Have they felt this threat in their own lives?

Approach and Considerations

The data presented in this update come from two nationally representative surveys: a first of 1,496 Canadians fielded between September 30th and October 4th, 2025, and a second of 1,503 Canadians fielded between October 30 and November 4, 2025.

The second survey contains a pair of experiments. The first experiment, used to evaluate support for political violence, exposes respondents to one randomized scenario about an individual sharing their political views targeting political opponents with either harassment, vandalism, assault, arson, or assault with a deadly weapon (in the form of a car attack). Each respondent only received one scenario (the exact wording is provided in the Methodology section at the end). Respondents were asked about their level of support for the attack in their randomized scenario and whether the perpetrator should serve jail time. For each of our questions asking about support for political violence, we restrict our sample to the 78% of respondents who were able to recall the nature of the violence in the vignette because prior research has found that support for political violence is inflated by respondent inattention.

The second experiment asks respondents “Which of the following actions, if any, do you believe are justified in response to public comments made about a violent political incident when those comments…” where the nature of the comments was randomized. Respondents either answered this question about speech that “justifies why the event occurred”, “celebrates or expresses approval of the event” or “encourages or promotes further violence.”

When describing the results, we will often draw attention to the “median” value among our survey respondents. This represents the response of the respondent in the “middle” of the data set. It is a useful value to track for questions when extreme responses may distort the calculation of average or mean responses.

1. How high is support for political violence in Canada, and how does it vary depending on the severity of the crime?

As shown in Figure 1, support for political violence is extremely low in Canada. When asked to place how justified it is “for people who share my political values and beliefs to use violence in advancing political goals these days” on a 0-10 scale, as illustrated in Figure 1, the respondents reported an average value of 0.8 with a median response of zero where 0 means “not at all justified” and 10 means “extremely justified.” 84% of respondents placed themselves at either 0 or 1 on that scale and 5% placed themselves above 5. In separate survey questions (not shown in Figure 1), 8% of respondents reported it was at least occasionally “OK for people who share my political values and beliefs to send threatening and intimidating messages to political opponents”, while 9% of respondents reported it was “OK for people who share my political values and beliefs to harass political opponents on the internet in a way that makes them feel frightened.”

These low numbers contrast with our IU3 finding that 21% of Canadians believe that political violence is sometimes necessary for social change, a view that reflects a broader, more distant judgment about the world and society. When specifically asked to evaluate whether people who share their political values are justified in using violence or intimidation, support drops dramatically. In other words, some Canadians may see political violence as sometimes necessary in the abstract or when it’s part of distant conflicts (e.g., people challenging repressive conditions abroad), but very few are willing to endorse violent or threatening actions when these are tied directly to their own political in-group.

Figure 1. Support for political violence on 0-10 scale. 0 means not at all justified, 5 means moderately justified, 10 means extremely justified.

Respondents were also asked about their level of support for a violent politically-motivated action and whether they believed the perpetrator deserved jail time. To understand how perceptions change based on the severity of the crime, each respondent was randomly shown a scenario involving one of five acts of violence: harassment, vandalism, assault with rocks, arson, or an attack with a deadly weapon. Figure 2 shows that support was low for the most serious acts: 3.4% indicated some support for the car attack and 4.3% supported arson, mirroring levels of support found in other democracies. Support is slightly higher for assault with rocks (9%) and vandalism (12%), and highest for harassment (25%).

In line with these low levels of approval, only a minority of Canadians oppose jail time for each of these crimes: 1-2% of respondents oppose jail time for the perpetrator for committing arson and a car attack, compared to 17% for assault with rocks, 30% for vandalism, and 26% for harassment.

Figure 2. Share of respondents supporting violent action (left) and opposing jail time for the perpetrator (right), with 95% confidence intervals.

2. Do Canadians overestimate their political opponents’ support for political violence? Are these misperceptions associated with their own willingness to endorse such actions?

While support for political violence is overarchingly low, there is variation in perceptions of support between partisan groupings. When asked where they think the average supporter of different parties and ideologies would place themselves on 0-10 scales of support for political violence (Figure 3), respondents placed far left-supporters at 1.6, the NDP and Liberals at 1, the Conservatives at 1.4, and far-right supporters at 2.2. Trump supporters were perceived to be the most accepting of violence at 2.5. The median response in all cases was zero (the median response is the middle value in the data set).

While perceived support is low, there is some evidence that perceptions of political support are exaggerated for political opponents – specifically left leaning voters overestimates the extent right-leaning voters support political violence more than the right does the left. As shown in Figure 3, Liberal and NDP supporters place Conservatives at 1.8 and 2.2 on the 0-10 scale, respectively, while Conservatives place themselves at 1.0, roughly 2x the true levels of support shown by Conservatives. Conservatives place Liberal supporters at 1.5 on the scale, while Liberals place themselves at 1, a 50% difference. Liberal and NDP supporters place far-right supporters at around 3 on the 0-10 scale, while Conservatives place them at 1.4. Placement of far-left supporters does not vary much by partisanship (between 1.6 and 1.9 on the 0-10 scale).

Figure 3. Perceived support for political violence on 0-10 scales across partisan and ideological groups.

Perceiving political opponents as supportive of violence is strongly correlated to one’s own support for violence. As shown in the left panel of Figure 4, an individual who believes out-party supporters place themselves at 10 (extremely justified) on the support for political violence scale supports the violence contained in the vignette at more than twice the rate of those who place their opponents at 1 on this same scale (20% vs. 9.7%). Similarly, as shown in the right panel of Figure 4, a person who places their political opponents at 10 on the scale, places themselves at 2.3 on the same scale. In contrast, those who believe out-party supporters place themselves at 1 on this scale, place themselves at 0.8 on this same scale.

Figure 4. Effect of perceived out-party support for political violence on percent of people supporting violent action in vignette (left) and average support for political violence on 0-10 scale (right). 95% confidence intervals.

3. What consequences do Canadians support for those who incite or justify political violence?

Canadians tend to report some support for combating political violence. 59% of respondents reported that “the government should take all necessary steps to prevent political violence even if it means infringing on some civil liberties”, while 41% agreed with the position that the “government should not infringe on civil liberties, even if it means accepting a greater risk of political violence. These findings suggest that Canadians give slight priority to preventing political violence over safeguarding civil liberties, highlighting the complex trade-offs policymakers have to consider.

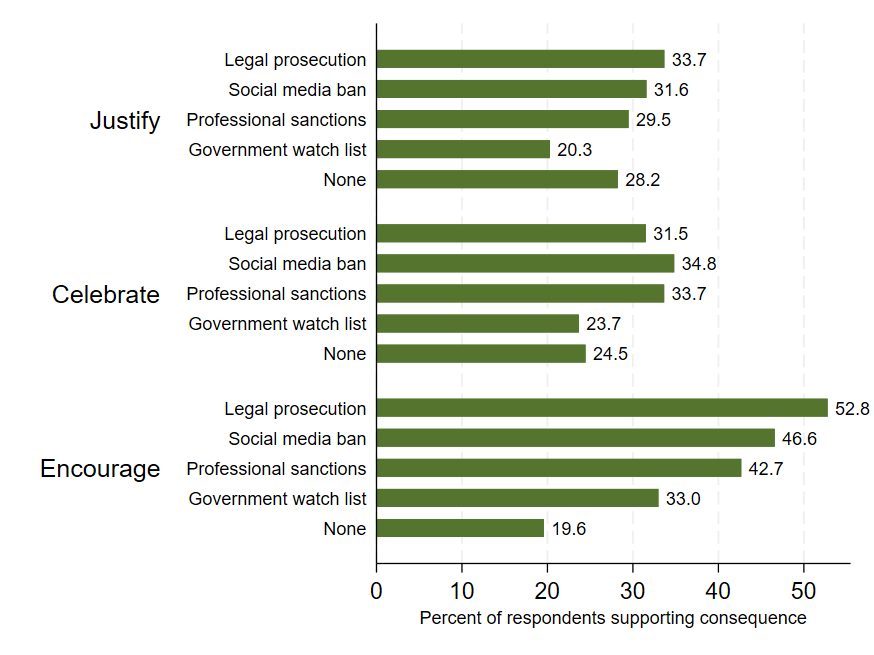

To better understand Canadians’ opinions on how society should punish political violence, we asked respondents to indicate what consequences would be appropriate for people who either justify, celebrate, or encourage political violence (which was randomly assigned to respondents). Respondents could select any number of consequences from a list that included, among others, professional sanctions (firing, suspension), legal prosecution, inclusion on a government watch list, a ban from social media platforms, and “none”.

Across all consequence types, support for sanctions is higher when speech encourages violence than when it celebrates or justifies it. Professional sanctions are supported by 30-34% of Canadians for those who justify or celebrate violence, compared with 43% for those who encourage violence. Similarly, between 32 and 34% of people believe legal prosecution is appropriate for those who justify or celebrate violence, which rises to 53% for those who encourage violence. A sizeable proportion of Canadians believe there should be no consequences for such speech – 24-28% when the speech celebrates or justifies violence, dropping to 20% for the incitement of violence.

Figure 5. Percent of respondents supporting four types of consequences for people who either justify, celebrate, or encourage political violence

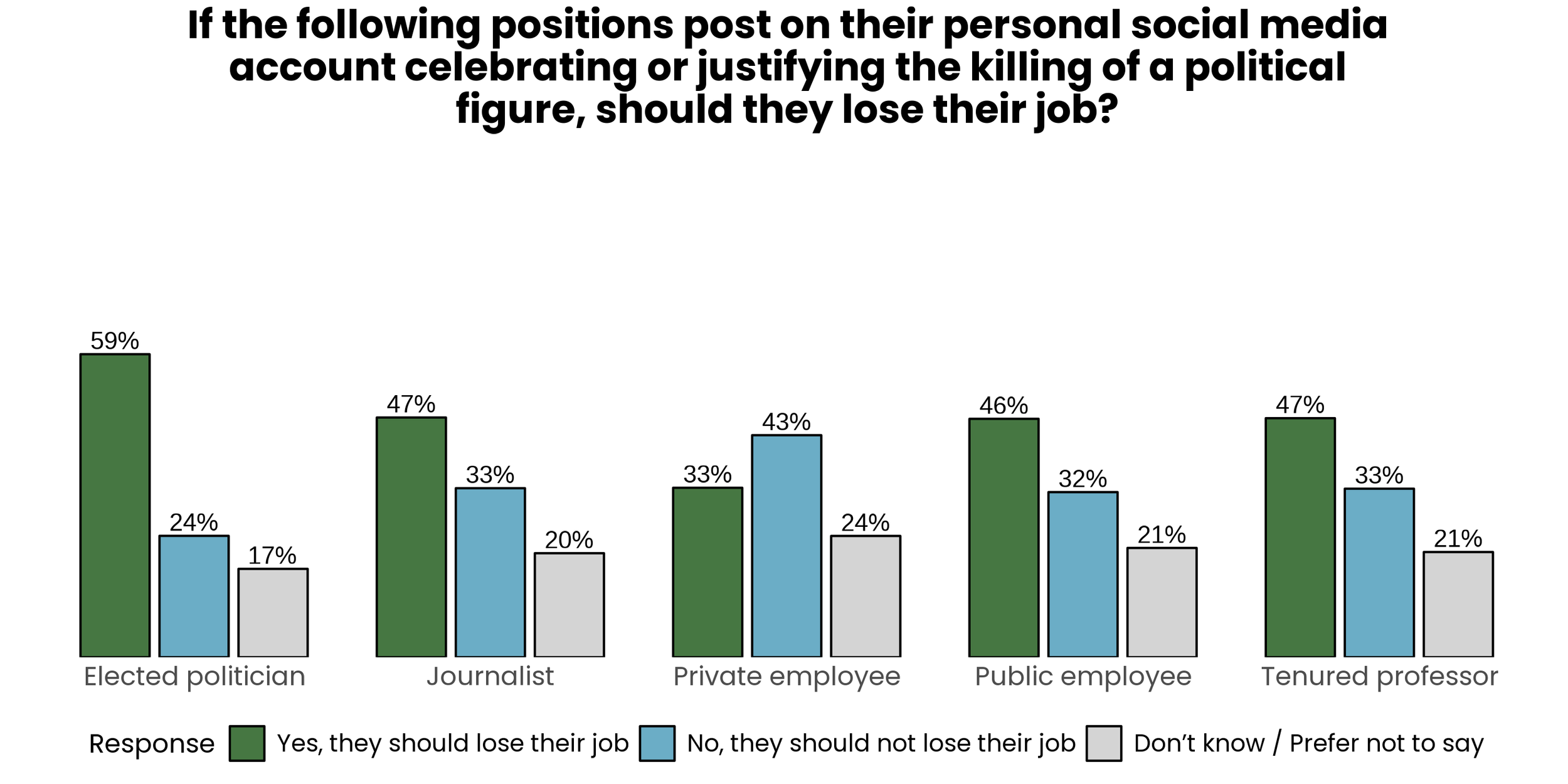

The tolerance for professional consequences for speech justifying or celebrating violence somewhat depends on the position of the person in question. As shown in Figure 6, 58% of Canadians believe an elected politician should lose their job, which drops to 46-47% for journalists, public employees, and professors. Only 33% believe a private employee should lose their job in this situation. These numbers are slightly higher than those observed by the Polarization Research Lab in the United States, where support for firing was 36-38% for journalists, public employees, and professors, and 31% for private employees.

Figure 6. Percent of respondents supporting job loss as a consequence for celebrating or justifying political violence by occupation type.

4. Do Canadians perceive freedom of expression to be under threat? Have they felt this threat in their own lives?

When asked about the degree to which they believe freedom of speech is threatened in Canada today, 56% say it is seriously or moderately under threat, though only 19% believe it is seriously under threat.

To examine how individuals assess the personal costs of posting political content online, we asked respondents “How often do you consider the following before posting (or declining to post) political opinions online?” including harassment, threats, or doxxing, job or professional consequences, social consequences, or legal consequences. As reported in Table 2, roughly half of respondents did not feel this was a relevant question since they have no interest in posting about politics on social media. Of the remainder, respondents were divided. 53% worry about harassment very or somewhat often. 54% worry about professional consequences, while 58% and 47% worry about social and legal consequences, respectively. This amounts to roughly 1/4 of the Canadian public.

Figure 7. How often respondents think of consequences before posting or failing to post political opinions online

However, very few Canadians report suffering personal consequences from their speech. As described in Figure 8, 79% report no consequences at all. 3-4% report suffering legal or professional consequences. The most frequently reported consequences were harassment and social conflict, which respectively 8% and 10% of Canadians say they experienced.

Figure 8. Percent of respondents experiencing consequences for expressing political opinions.

These findings broadly align with IU3, where about half of respondents reported no change in their political behavior due to concerns about political violence, while about one quarter indicated they would avoid posting opinions on social media, attending protests, or putting up political signs for that reason. The relatively low numbers of Canadians reporting actual negative consequences for their speech may not indicate the absence of risk, but could also reflect chilled speech, with some individuals avoiding expressing their political opinion out of concern for potential repercussions.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that an overwhelming majority of Canadians are opposed to all forms of political violence by people who share their political views, though it’s troubling that this opposition softens somewhat towards harassment directed towards political candidates. They also mostly believe different partisan and ideological groups categorically reject political violence, though do tend to underestimate the extent to which political violence is rejected by their partisan or ideological opponents. This could be a driver of support for political violence or reflect projection effects where people predisposed towards violence project that support onto their political opponents.

Canadians are somewhat willing to trade off civil liberties to combat political violence but overall, they are somewhat divided. An overwhelming majority of Canadians believe there should be some consequences to speech that celebrates, justifies or encourages political violence – where most support legal prosecution or professional sanctions of those who incite violence (e.g. engage in acts that encourage violence). Support diminishes when the speech in question celebrates or merely justifies such violence.

At tension with these findings is the reality that the majority of Canadians believe freedom of expression in the country to be threatened to some degree. Notwithstanding this belief, only a minority of people report a reluctance to express themselves in online spaces because of possible consequences (though it’s roughly half of people that actively engage in online political discussion). More importantly, extremely few Canadians report having experienced consequences from expressing themselves. For many Canadians, the threat perceived to freedom of expression appears to be rooted more in the fear of potential repercussions and self-censorship than in actual, lived experiences of consequences.

Methodology

Harassment: Imagine that a person was convicted of harassment and uttering threats. This individual has political views similar to your own. He was arrested for repeatedly communicating threatening and hostile remarks to a political candidate from a political party you oppose over the period of a year on social media.

Vandalism: Imagine that a person was convicted of vandalism. This individual has political views similar to your own. He was arrested for smashing the windows of a local homeowner who was a known activist for a political cause you oppose. The action caused approximately $2000 in property damage.

Assault: Imagine that a person was convicted of assault. This individual has political views similar to your own. He was arrested by police for throwing rocks at peaceful protesters in favour of a political cause you oppose. Although no one was seriously injured, paramedics bandaged a man with a head wound.

Arson: Imagine that a person was convicted of arson. This individual has political views similar to your own. He was arrested by police as he attempted to run from a fire he started at the local headquarters of an organization that supports a political cause you oppose. Although he waited for the building to close for the night, several adjacent buildings were still occupied.

Assault with a deadly weapon: Imagine that a person was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon. This individual has political views similar to your own. He was arrested by police after driving his car into a crowd of protesters in favour of a political cause you oppose. Although no one was killed, several individuals were seriously injured and one spent a month in the hospital.