Incident Update 3︱Shared anxiety, different lenses: Comparing Canadian and American perceptions of political violence

Authors & Organization

Chris Ross, Mathieu Lavigne, Esli Chan, Diya Jiang

Organization: Media Ecosystem Observatory

Key takeaways

Shared recognition that political violence is serious, but Canadians view it as a much greater problem in the United States: Most Canadians and Americans view Charlie Kirk’s assassination as part of broader societal problems, agree political violence is a serious problem in the U.S., and expect it to worsen. Canadians perceive political violence as far more pressing in the U.S. than at home, both in seriousness (89% vs. 50%) and expected worsening (62% vs. 35%).

Partisan patterns differ across borders in the perception of political violence: In the U.S., Democrats are the most pessimistic about political violence worsening (86%), while in Canada, the highest concern comes from those who identify as Conservatives (50%).

Young Canadians are more likely to see political violence as a means to achieve social change: 33% of Canadians aged 18–34 view political violence as sometimes necessary for social change, potentially reflecting growing frustration with conventional political channels of representation.

Concern about political violence deters democratic participation: Roughly half of Canadians and Americans surveyed report they will avoid at least one form of political participation, such as putting up political signs, posting opinions online, or attending protests, because of concern about political violence.

Introduction

Charlie Kirk’s assassination, an act of political violence, intensified national debate about polarization and free speech. Following his assassination, there has been a marked increase in public discourse around perceptions of threat, justification, and consequences of political violence in Canada and the U.S. In this incident update, we examine public attitudes towards political violence, assessing whether the incident and ensuing debates are perceived by Canadians as a shared concern or a uniquely American issue.

Key questions

This report evaluates the following research questions, drawing comparisons with U.S. data where available:

Is Charlie Kirk's assassination perceived as an isolated incident?

How concerned are Canadians about political violence?

To what extent do Canadians believe political violence can be justified?

Does concern about political violence impact participation in public life?

Approach and Considerations

To understand American attitudes in our comparative analysis, we replicate and extend survey research by the Polarization Research Lab (to be referred to as PRL onwards) conducted the week after Kirk’s shooting in Canada. Their data is from a nationally representative sample of 1000 Americans and is indicated by an asterisk (*) in any plots throughout this update. In one section, we also cite data from a representative survey of 2101 Canadians conducted by the Digital Public Square in 2024 to show possible time trends in the Canadian context.

Our analysis of Canadian attitudes is based on original survey data from a nationally representative sample of 1,496 Canadians, fielded between September 30th and October 4th, 2025, and largely replicates the PRL question set. To ensure that respondents had a shared understanding of political violence, we began our question block on political violence by providing the following definition:

“By political violence, we mean acts of physical harm, threats of physical harm, or damage to property that are carried out on purpose to influence politics or achieve political goals.”

The following analysis should be read with this definition in mind.

1. Is Charlie Kirk's assassination perceived as an isolated incident?

Online conversations about Charlie Kirk’s assassination have been wide-ranging. One facet centered on whether the incident was an isolated event or whether it was part of a longer history of politically—motivated acts of violence, in a context of rising polarization and declining trust in democratic institutions.

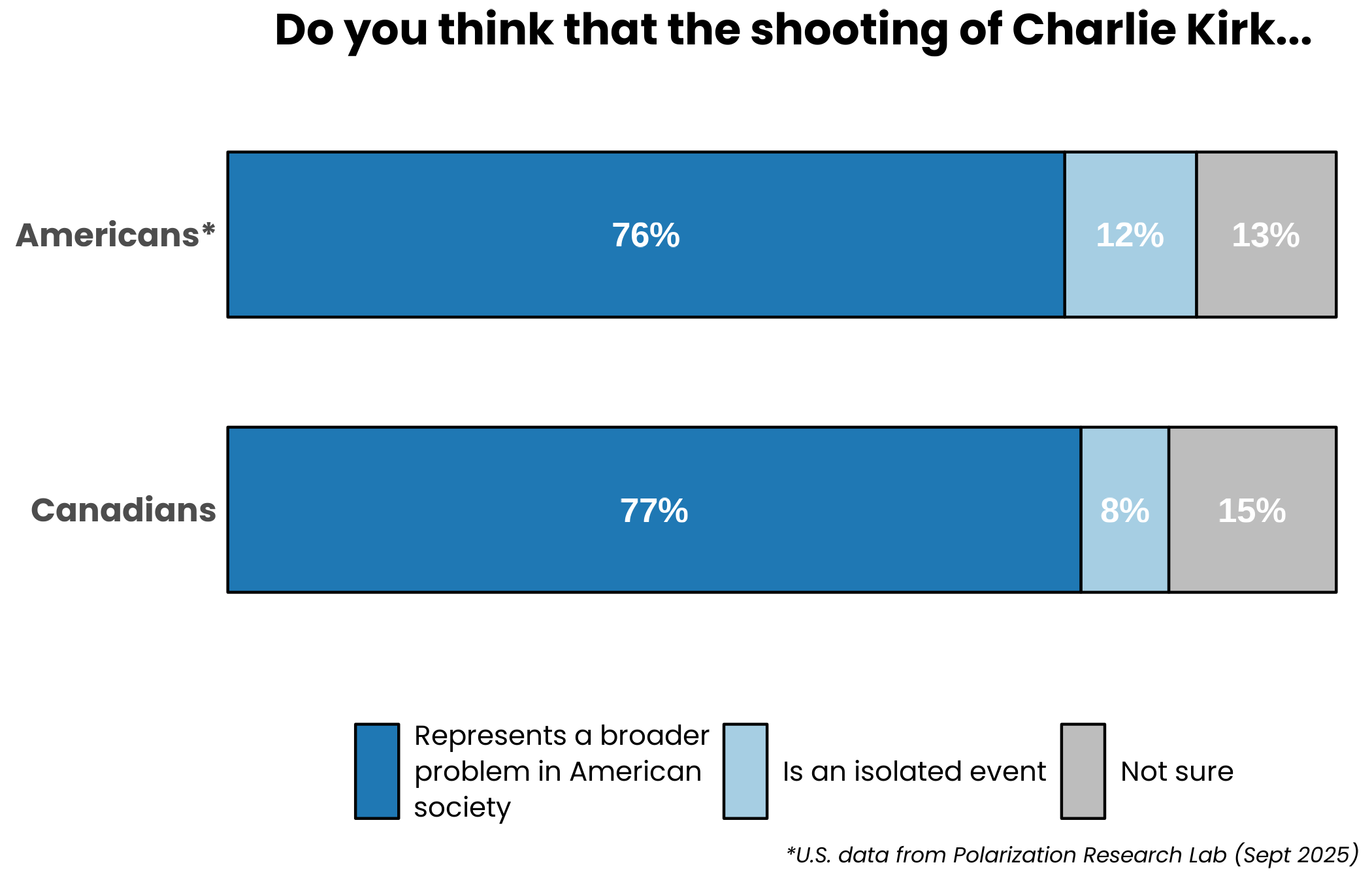

To assess whether Canadians share Americans’ assessment of the incident, we replicated PRL’s survey question, asking whether the shooting of Charlie Kirk represents a broader problem in American society or is an isolated event. Figure 1 shows that more than 3 in 4 Americans found the incident to be representative of a “broader societal problem,” a view shared by a similar proportion of Canadians (77%). Only a small minority considered it an isolated event (Canada: 8%; U.S.: 12%) or were unsure (Canada: 15%; U.S.: 13%). Simply stated, Canadians and Americans are aligned in viewing Kirk’s death as a part of a larger problem in the U.S. and not a one-off tragedy.

Figure 1. Comparing Canadian and American views on whether Charlie Kirk’s assassination reflects a broader societal problem

2. How concerned are Canadians about political violence?

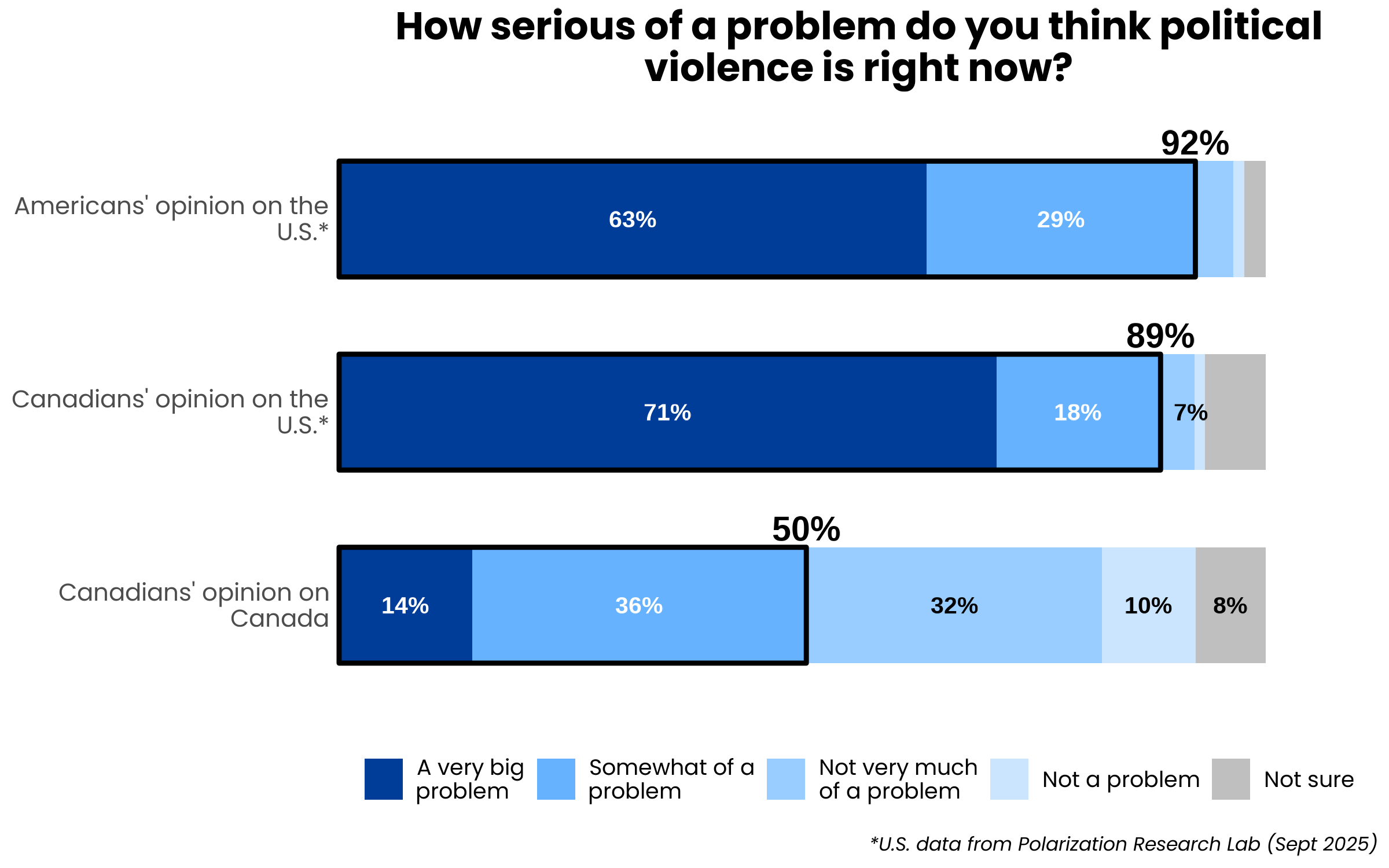

When directly asked whether political violence is a serious problem, Canadians’ and Americans’ assessment of the U.S. is strikingly similar. As Figure 2 illustrates, 89% of Canadians think political violence is a ‘somewhat’ or a ‘very big’ problem in the U.S., a proportion statistically indistinguishable from the 92% of Americans who view it that way. The notable difference lies in Canadians’ assessment of Canada: using the same measure, only half (50%) consider political violence a serious problem in Canada.

Figure 2. Comparing Canadian and American perceptions of the threats posed by political violence

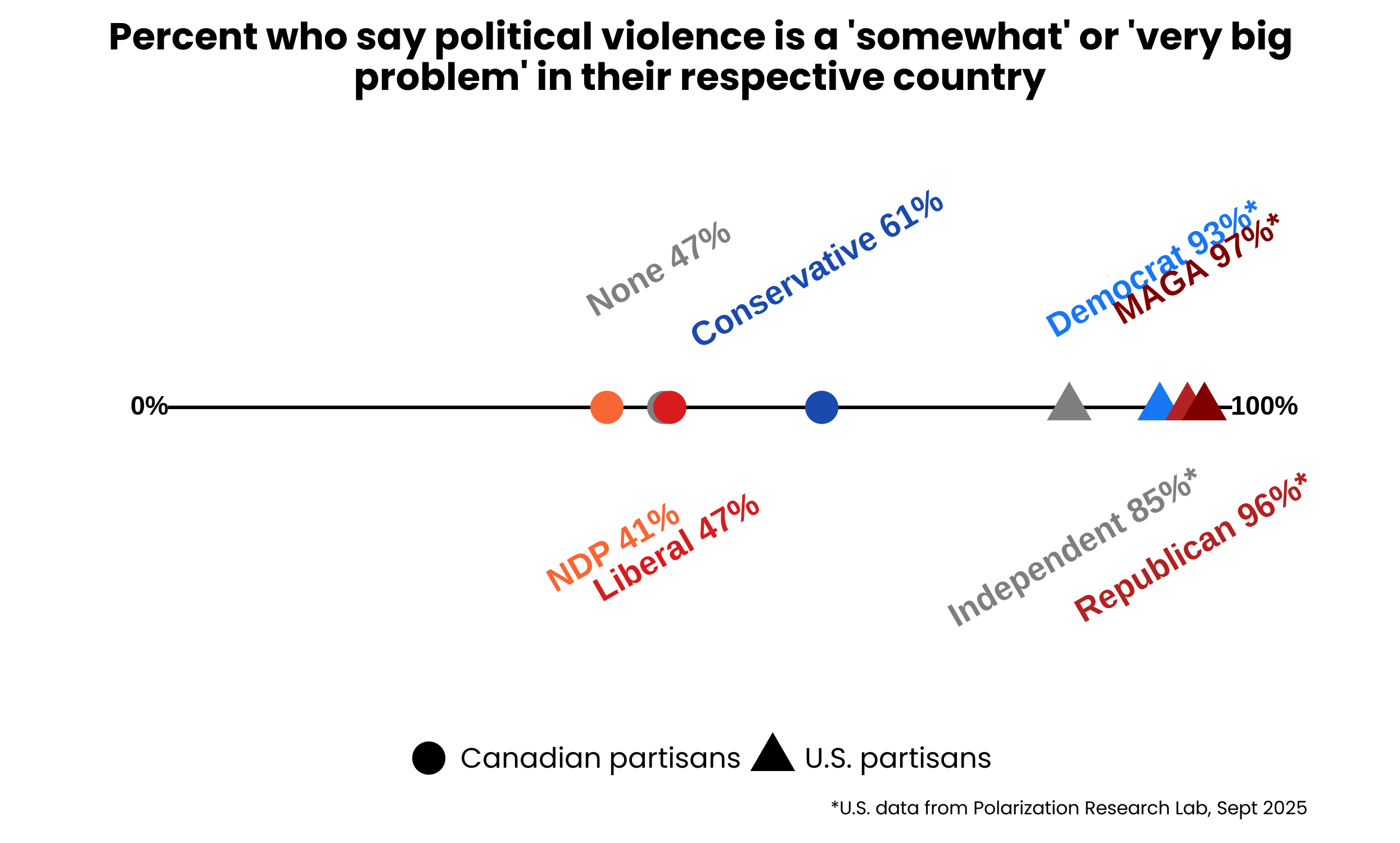

Using the same survey question, we next examine partisan differences in Canadians' and Americans’ perceptions of political violence in their respective country. Figure 3 shows that all respondents grouped by partisanship in the U.S. overwhelmingly believe that political violence is a serious problem (93-97%) while the Independents are the least likely to do so (85%). In Canada, concern is generally lower, but Conservatives are significantly more likely to view political violence as a serious problem (61%) as compared to Liberals, New Democrats, or those with no party affiliation (43–48%). Overall, in the post-Kirk assassination period, left-partisan individuals are less likely than right-partisan counterparts to view political violence as a serious issue, particularly in Canada.

Figure 3. Partisan breakdowns of Canadian and American perceptions of the threats posed by political violence

Next, we examine whether Canadians and Americans expect political violence to get better or worse in the coming years. Figure 4 shows Americans are the most pessimistic about the future of political violence in their own country, with 76% thinking the problem will worsen. Canadians are slightly less pessimistic about the U.S.’s future, though a majority also expect the situation to get worse (62%). Turning to their own country, 35% think political violence will worsen, while nearly half (46%) expect it to remain about the same. These patterns show that Canadians’ expectations differ sharply depending on whether they are considering political violence in the U.S. versus Canada.

Figure 4. Comparing Canadian and American assessments of whether political violence will get worse or better in the next few years

Figure 5 evaluates partisan differences in expectations about whether the problem of political violence will get better or worse in the coming years. In the U.S., Democrats are more likely than Republicans to believe that the problem will worsen (86% versus 68%), while in Canada, Conservatives are more pessimistic than the Liberals (50% versus 28%). These differences are more pronounced than those observed in Figure 3 (general perception of political violence as a problem), suggesting that perceptions of future safety and stability are more tied to partisanship.

Figure 5. Partisan breakdowns of Canadian and American assessments of whether political violence will get worse or better in the next few years

3. To what extent do Canadians believe political violence can be justified?

Political violence is often discussed in highly charged contexts, where individuals navigate a tension between democratic norms opposing violence and social media discourse praising certain acts of political violence. For example, in December 2024, Luigi Mangione murdered a U.S. healthcare company CEO. His actions were widely discussed on social media, with much of the content glorifying him as a vigilante.

Figure 6 examines changes in Canadians’ views on whether political violence is sometimes necessary for social change, comparing responses after the Charlie Kirk incident with those collected by the Digital Public Square (DPS) in the summer of 2024. The proportion expressing this belief increased slightly from 16% in 2024 to 21% in 2025, but remains close to previous levels (20% in 2023), indicating overall stability in Canadians’ rejection of political violence.

Our data show significant age differences, slightly larger than those identified by the Digital Public Square. Between 2024 and 2025, the share of Canadians aged 18-34 who consider political violence sometimes necessary rose from 26% to 33%, compared with smaller increases among Canadians aged 35–54 (17% to 21%) and those 55 and older (11% to 12%). It is important to note that respondents may have had different forms of violence in mind — ranging from property damage to physical harm — which carry very different implications. That said, these findings invite reflection on how the legitimacy and effectiveness of democratic processes can be strengthened, and on whether those who see political violence as necessary for social change would instead rely on democratic levers if they trusted their efficacy. An underexplored area of this analysis is whether Canadians believe these levers provide real opportunities for change or view political violence as a ‘first-choice’ mechanism.

Figure 6. Canadian perceptions of whether political violence is sometimes necessary for social change over time and by age group

4. Does concern about political violence impact participation in public life?

Political violence can have wider societal effects by discouraging people from participating in public life. Figure 7 compares how often Canadians and Americans (the latter measured by the Polarization Research Lab) report avoiding certain activities due to concerns about political violence.

Figure 7. Comparing Canadian and American self-reported likelihood of avoiding political activities due to concerns about political violence

The most notable finding is that about half of respondents, in both Canada and the U.S., report not changing any of their listed behaviors because of political violence. However, that leaves half the population who express concern about political violence resulting in decreased political engagement. Combined with findings from Figures 2 and 4, this highlights a tension between perception and behavior: Canadians see political violence as a greater problem in the U.S. than Canada, but report avoidance of public participation at rates similar to Americans. This underscores that despite differing perceptions of political violence, Canadians and Americans face a similar climate of caution and self-censorship that limits open civic participation.

In Canada and the US, about one quarter of the population express concern in engaging in acts of political expression due to political violence. These actions include putting up political signs (28 vs. 31%), posting political opinions on social media (28%-30%) or attending a protest (23%-27%), with no meaningful difference between Canadian and American attitudes. Though a small figure, 6% of Canadians report that they will avoid voting in an election due to concerns about political violence. Together, these findings expose a serious strain on democratic participation.

Political violence can thus cause a chilling effect, both online and offline, discouraging people from engaging in visible political action. One additional action we examined—not included in the PRL survey—is the willingness to become a public figure. While few Canadians actually face this choice, citizens’ willingness to take on a public role is a vital dimension of a healthy, participatory democracy. Alarmingly, about one in five Canadians (21%) report that concerns about political violence make them likely to avoid becoming a public figure. When fear of political violence dissuades Canadians from pursuing political office or engaging publicly, it weakens the inclusivity of voices in democratic discourse and erodes the resilience of democratic institutions.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that Canadians and Americans share a deep concern about the state of political violence and its broader social implications. The vast majority in both countries see the Charlie Kirk assassination as a reflection of wider societal problems. 9 out of 10 Canadians and Americans agree that political violence is a major issue in the U.S. and that the situation is likely to get worse in the coming years across the board.

At the same time, our results reveal significant partisan divides across the border. In both countries, people from the opposition party (Democrats in the U.S. and Conservatives in Canada) express greater pessimism about the future of political violence, suggesting that such views can be tied to trust in the current leadership. Although Canadians across age groups generally reject political violence, younger adults stand out for viewing political violence as potentially necessary for social change. Moreover, citizens in both countries report avoiding democratic expression due to concerns of political violence. Together, these patterns indicate that the shadow of political violence shapes how people perceive the state of their democracy, dissent, and political participation.

Feature Image: Charlie Kirk speaking with attendees at The People's Convention at Huntington Place in Detroit, Michigan, by Gage Skidmore, is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.